By Lal Khan

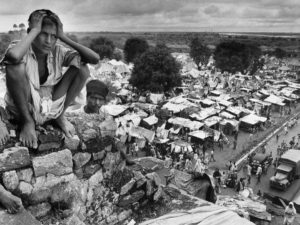

On August 14 and 15, this year, Pakistan and India’s ruling classes will be organising extravagant mass celebrations for their 70th anniversaries of independence. However, what happened in August 1947 was one of the most atrocious genocides of the twentieth century. Some independent researchers put the figure at almost 2.7 million people slaughtered in the insane frenzy of religious hatreds unleashed by the partition of the South Asian subcontinent. There was an enforced migration of over twenty million souls, uprooted from the ancestral homes and hearths where they had been living for centuries if not millennia. They were compelled to venture on to perilous journeys to unknown destinations and destinies across the Radcliff line – the artificial line, drawn by a British bureaucrat who had never even visited India before, to cleave the subcontinent and spill innocent blood.

Lapierre and Collins have sketched the baseness of the communal bestiality of partition in their work “Freedom at Midnight.” In one episode, they narrate the plight of women victims of this madness: “If they were Sikh or Hindu, a woman’s abduction was usually followed by a religious ceremony, a forced conversion to make a girl worthy of her Muslim captor’s auctioned possession in his home or harem… The Sikhs’ tenth Guru (Gobind Singh 1666-1675) had specifically enjoined his followers against sexual intercourse with Muslim women. The inevitable result was a legend among the Sikhs that Muslim women were capable of particular sexual prowess. Under the impact of events in the Punjab, the Sikhs forgot the Guru’s admonishment and gave free reign to their fantasies. With morbid frenzy, they fell on Muslims everywhere, until a trade in kidnapped Muslim girls flourished in their parts of the Punjab.”

It was a criminal division perpetrated by the British imperialists in connivance with the native elite classes and politicos. Colonial rule in India by the British Raj had lasted for more than two hundred years. Once forced by their historical decline to withdraw, the British imperialists executed the policy of divide and rule, they had learned from the ancient Roman Caesars. The British imperialists were determined not to leave behind a united India. Churchill had described Hindu-Muslim antagonism as, “a bulwark of British rule in India…Were it to be resolved, their concord would result in the united communities joining in showing us the door.” The role of the Hindu and Muslim aristocracy and capitalist comprador elites grafted together as the ‘national bourgeois’ by their British masters was no less treacherous. Leon Trotsky brilliantly explained the real character of this native ruling class, whose most renowned leader abroad was Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. Trotsky wrote in 1939:

“The Indian bourgeoisie is incapable of leading a revolutionary struggle. They are closely bound up with and dependent upon British capitalism. They tremble for their own property. They stand in fear of the masses. They seek compromises with British imperialism no matter what the price. The leader and prophet of this bourgeoisie is Gandhi. A fake leader and a false prophet… Double chains of slavery — that will be the inevitable consequence of the war if the masses of India follow the politics of Gandhi, the Stalinists and their friends.”

Gandhi gave an impetus to religious chauvinism. He cunningly brought spiritual prejudices to the centre of politics, stirring up chastising, divisive and belligerent passions. Hindu xenophobic organisations had rarely been present in the political mainstream before Gandhi. With his covert incitement, religiosity infiltrated politics, often under the guise of “interfaith harmony”. Organisations such as the Hindu Mahasabha and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sang fomented the perception of a Hindu nation in that period. The retreat of class struggle, particularly after the defeat of the1946 revolt and general strike, promoted religious jingoist tendencies in society.

The role of the Muslim political elite in the liberation movement was in no way less reactionary than Gandhi’s. The ebbing of the tide of class upheaval led to religious domination in politics. In the second decade of the twentieth century, Jinnah had warned Gandhi of the danger of mixing religion with politics. It’s a historical irony that he is hailed as the father of Pakistan, which, despite Jinnah’s secularist rhetoric, was in its fundamental conception a theocratic state. On January 28, 1933, Jinnah had ridiculed the notion of Pakistan, calling it “ an impossible dream”. A decade later, Jinnah presided over a party that exploited religious bias to win electoral contests.

Such malicious fervour was whipped up that the arguments over the division of assets and the lust for possessions during partition became absurd and crazy. The Islamists wanted the Taj Mahal broken up and shipped to Pakistan because a Moghul had built it. The Hindu chauvinists insisted that the Indus River flowing through Pakistan should somehow be theirs because their sacred Vedas were supposedly written on its banks more than two millennia ago.

In the last analysis, independence was not won through a fight against imperialist rule but through agreements and rotten compromises within the native political elite in mortal fear of a socialist revolution from below. Partition, in reality, was a counter-revolution. A year before this gory separation, there was a revolutionary upheaval in the subcontinent against the British Empire. It was triggered by the revolt of the sailors of the Royal Indian Navy, generally known as the Great Indian Navy Mutiny 1946, when 1100 sailors on HMIS Talwar stopped work and declared an official strike at dawn of February the 18th.

The sailors unanimously elected as their representatives, Signalman M.S Khan, petty officer telegraphist Madan Singh and signaller Bedi Basant Singh – a Muslim, a Hindu and a Sikh, consciously rejecting the religious fervour being instigated by the British and their colonial toadies in that period. The strike that began at Bombay harbour spread like wildfire to military establishments in Karachi, Madras, Vishakhapatnam, Calcutta, Delhi, Cochin, Jamnagar, and the Andaman Islands, and on to Bahrain and Aden on the shores of the Middle East. Gandhi condemned this uprising outright, and Jinnah rejected it as unconstitutional. Congress and the Muslim League were afraid of the revolutionary character of the movement and the class struggle cutting across the religious divisions they were sowing in the independence movement. They overtly and covertly intrigued to crush the revolt.

At 06-00 hours on 24 February 1946, black flags were raised to announce surrender. In its last session, the strike committee passed a resolution that stated:

“Our uprising was an important historical event in the lives of our people. For the first time, the blood of uniformed and non-uniformed workers flowed in one current for the same collective cause. We, the workers in uniform shall never forget this. We also know that you, our proletarian brothers and sisters shall also never forget this. The coming generations, learning its lessons shall accomplish what we have not been able to achieve. Long live the working masses. Long live the Revolution.”

In fact, the British were forced to retreat from India by decades of strikes, mass demonstrations, and daring and heroic armed struggles like those of Bhagat Singh and his comrades of the HSRA (Hindustan Socialist Revolutionary Association). There were also increasing revolts within the police, air force and army, and mass insurrections from Calcutta to Karachi and Delhi to Colombo. Industrial strikes had rapidly spread across Bombay, Calcutta, Allahabad, Delhi, Madras, Karachi and several other major cities. The rebellion defied massive state oppression, arrests, tortures and even the use of live ammunition. India’s virgin proletariat played a crucial role in the liberation struggle.

The vice president of the naval revolt’s Central Strike Committee, Madan Singh, in an interview with the Tribune (a Chandigarh-based newspaper) many years later illustrated the revolutionary situation prevailing in the Indian subcontinent at the time: “After the outbreak of the mutiny, the first thing that we did was to free B. C. Dutt (who was arrested during General Auchinleck’s visit). Then we took possession of Butcher Island (the entire ammunition meant for Bombay Presidency was stocked) and Kirkee near Pune. Our quick actions ensured that all the 70 ships and all the 20 seashore establishments were in our control. We had secured control over the civilian telephone exchange, the cable network and, above all, over the transmission centre at Kirkee manned by the Navy, which was the channel of communication between the Indian Government and the British.”

P.V. Chakraborty wrote in March 1976: “When I was acting as Governor of West Bengal in 1956, Lord Clement Attlee, who as the British Prime Minister in post war years stayed in Raj Bhavan, Calcutta. I put it straight to him like this: ‘The Quit India Movement of Gandhi practically died out long before 1947 and there was nothing in the Indian situation at that time which made it necessary for the British to leave India in a hurry. Why then did they do so?’ In reply, Attlee cited several revolts including the INA (DR. Subhash Chandra Bosh’s rebel army) and the RIN mutiny, which made the British realise that the Indian armed forces could no longer be trusted. When asked about the extent to which the British decision to quit India was influenced by Mahatma Gandhi’s 1942 Quit India movement, Attlee’s lips widened in a smile of disdain and he uttered, slowly, ‘Minimal’.”

However, it was the criminal role played by the Comintern under Stalinist domination from Moscow and the leadership of the CPI under its tutelage that ensured the failure to provide a revolutionary path, leadership and strategy to the mass revolutionary upsurge. They initially supported the British imperialists during the second half of the world war under the pretext of ‘fighting fascism’; and later they pursued the disastrous policy of forming ‘people’s fronts’ with what they termed the “progressive bourgeoisie” of both Congress and the Muslim League varieties, that aborted the revolution and led to the horrors of partition. They cannot be historically exonerated of their role in this tragedy of partition that has brought coercion, misery, poverty, devastation and harrowing sufferings for generations numbering more than one fifth of the human race ever since.

The South Asian subcontinent was the cradle of the Indus valley civilisation -the oldest in the world. This heritage and the subsequent relatively prosperous societies that followed have contributed immensely to the development of human knowledge in various fields of science, culture and the arts. The literary history encompasses some of the greatest works of poetry and prose. In ancient times, the South Asian subcontinent was known as the land “flowing with milk and honey” because of its advanced economy and agriculture. After the fall of Rome, whilst Europe languished in the dark ages, the subcontinent’s economy, society, arts and culture flourished. Many invasions occurred in almost three millennia, but all the invading tribes and dynasties were absorbed by the rich culture and fertility of its land. The British were the first that did not.

However, due to the intrinsic conservatism and lethargy of the wealthy monarchical elites, India’s growth, innovation and development had stagnated and fell behind Europe in the second half of the last millennium. After the industrial revolution, the West had developed superior scientific, militaristic and technological skills, products and instruments. This allowed the West to exert its superiority over the obsolete technological, state and social structures in India. British colonisation resulted in new forms of plunder, with the native industries, economies and cultures systematically destroyed and the region’s wealth robbed for imperialist profits.

On the seventieth anniversary of this elusive independence, the masses are still in chains. The sub-continent’s reactionary ruling classes are still pursuing the policies of religious hatreds and nationalist jingoism that led to the bloody partition of 1947. The states’ military and civilian bureaucracies are using this animosity to loot the meagre resources of these societies. The capitalists and the remnants of the landed aristocracies are inflicting rabid exploitation to amass wealth. The Islamic and Hindu fundamentalist barons are marketing their sectarian venom to linger this orgy of plunder. The bosses of black capital stuffing their coffers with criminal dough orchestrate terrorism and religious sectarian bloodshed.

On the seventieth anniversary of this elusive independence, the masses are still in chains. The sub-continent’s reactionary ruling classes are still pursuing the policies of religious hatreds and nationalist jingoism that led to the bloody partition of 1947. The states’ military and civilian bureaucracies are using this animosity to loot the meagre resources of these societies. The capitalists and the remnants of the landed aristocracies are inflicting rabid exploitation to amass wealth. The Islamic and Hindu fundamentalist barons are marketing their sectarian venom to linger this orgy of plunder. The bosses of black capital stuffing their coffers with criminal dough orchestrate terrorism and religious sectarian bloodshed.

The toiling masses have suffered for generations. According to a UNICEF report, the health conditions of the masses are far worse today than they were at the time of the 1857 Indian War of Independence. This region has almost twenty percent of the world’s population, yet it hosts more than 40 percent of the planet’s poverty. These are two nuclear-armed states, yet 44 percent of children suffer from stunted growth due to malnutrition. The ruling classes in India and Pakistan have failed to carry out the tasks of creating modern industrialised nation-states. None of the tasks of the national democratic revolution has been completed. They are among the top ten buyers of weaponry, and amongst the lowest spenders in health and education provisions. Hindutva chauvinists now rule the so-called ‘largest democracy’ in the world, India, while in Pakistan the ruling classes use religion to coerce the toiling masses with the terror of Islamicist black reaction. Its military establishment thrives on this religious chauvinism.

At the peak of the Mughal rule in 1577, when Akbar was on the throne, the Indian subcontinent stretched from Kabul in the west to Rangoon in the East. These countries, now carved out as separate states from the Indian subcontinent, were created by imperialism to expedite imperialist coercion and robbery. To the north, the sub-continent is separated from Tibet and China by the McMahon line proposed by Henry McMahon in 1914. In the west, Afghanistan was bifurcated by the so-called Durand Line, drawn in 1893. Similarly, Burma was severed from the sub-continent’s territory in 1937 by the Indo-Burma barrier. The Radcliff line bifurcated Nepal, Punjab and Bengal and sliced out new states. These partitions have obliterated the India that once was. What we have now are the bifurcated states of Pakistan, Bharat, Bangladesh and others. Within the confines of these imposed imperialist enclosures, the great civilisations of Indus and the Ganges along with their tributaries are strangled and traumatised.

Vast sections of the populace have sunk into a bottomless pit of misery and poverty. A cursory look at the industrial infrastructure and the conditions of the masses negates and condemns the rulers’ claims of development and growth. On the basis of partition, India and Pakistan developed as two separate countries, but to this day, the ruling class of neither country has not been able to solve any of the seething problems faced by the masses. The subcontinent is in a state of ferment.

In these seventy years, we have witnessed glorious struggles of the youth and the working classes against these tyrannical states and socio-economic systems. From the Afghanistan’s Saur revolution of spring 1978 to the revolutionary movement of 1968-69 that challenged the existent property relations in Pakistan, there have been relentless struggles of the oppressed classes to transform society. Stormy events loom large on the horizon. A new mass revolt can lead to a victorious insurrection. A victory of the workers, youth and the poor peasants in any regional country shall inevitably spread the revolutionary wave throughout the South Asian subcontinent. Revolutions do not just transform the economies and the states; they also change the course of history and geographies of the decayed and reactionary capitalist states. A revolution in this region will smash the artificial frontiers propped up by the imperialists and their local bourgeois toadies. With the triumph of the revolutionary masses, this criminal partition shall be undone. Such a historical leap will unite more than one and a half billion oppressed human souls into a voluntary socialist federation of South Asia.